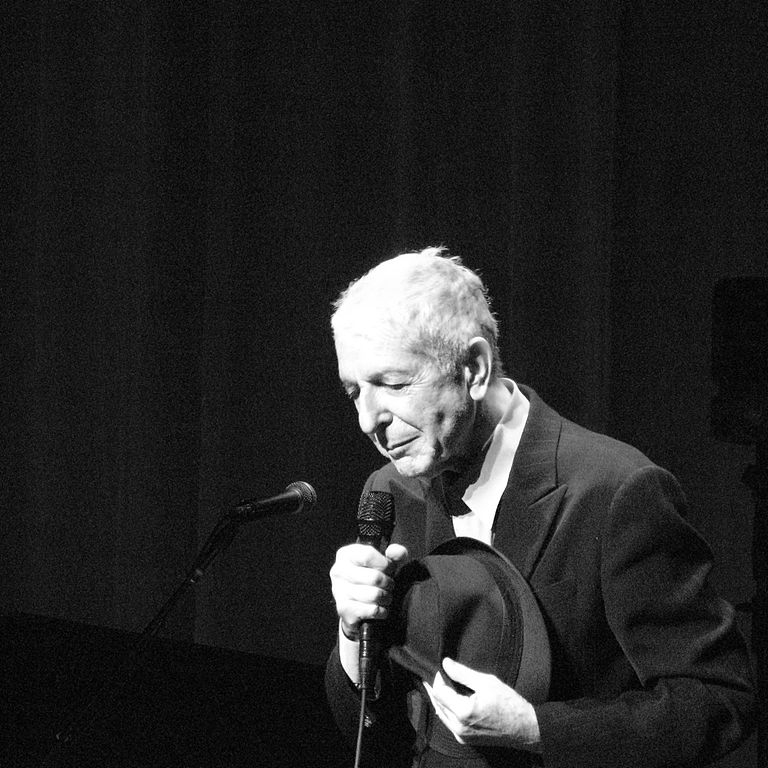

Leonard Cohen

You Want It Darker

Album Release Date: October 21st, 2016

Columbia Records 2016 - Image via leonardcohen.com

Leonard Cohen is one of several major celebrities who passed away in 2016, and like David Bowie and Phife Dawg of A Tribe Called Quest, he also released a final album of original material the same year he died. However, unlike Bowie and Phife, both of whom recorded their last albums in secrecy and released them to fans' surprise and delight, Cohen's album was expected. Less than three weeks after the release of You Want It Darker, Cohen's 14th studio album, he passed away at age 82, on November 7th, 2016.

As a celebrated singer-songwriter whose spiritual, romantic songs continually resonated with audiences throughout his over 50-year career, news of Cohen's death was certainly impactful if not ultimately less of a shock than Bowie's, who managed to keep his cancer private and out of the press, and Phife who—while openly diabetic for years—was nonetheless very young to pass due to complications from the illness at 45. But Cohen had been vocal about his deteriorating health of late, suffering from multiple fractures of the spine, and commented in a recent New Yorker interview that he'd been in considerable physical pain for a long time and was "ready to die". But in a later Billboard interview he said, "I think I was exaggerating. I've always been into self-dramatization. I intend to live forever." A month later he was dead. The final moment came after Leonard had a fall in the night and subsequently died in his sleep. An appropriately ironic time for him to die—at night, in the dark—given the prominent metaphorical applications of light and dark on his closing work. Since his health prevented him from moving around much, the album was produced by his musician son Adam Cohen and mostly recorded in Leonard's Los Angeles home with contributing musicians adding their parts via internet correspondence.

Leonard Cohen has been lauded as a poet whose lyrics encapsulate romantic longing, emotional honesty, spiritual enlightenment, and pleas for forgiveness, compassion, and love. He was a hard-loving troubadour whose sensitivity to the suffering of others was matched only by the intensity with which he expressed and described lovemaking—whether yearning for love unrequited, reveling in love fulfilled, or reminiscing on love passed. And while his songs have usually been downtempo and sad, his dreamy, hypnotic folk music-poetry took on another dimension mid-career with occasional turns to a more ironic, cynical sensibility. Some of the aforementioned qualities remained, but songs like "First We Take Manhattan", "Everybody Knows", and "The Future", showed a shift in attitude of Cohen's narrator. At this time (the 1980s and '90s) his songs took on more overt political undertones with pieces like "Democracy" (from 1992's The Future) and "The Land of Plenty" (from 2001's Ten New Songs), but the sarcasm lessened after that as he returned to the voice of a sensitive emoter for his last few albums. Despite Cohen's advanced age, he'd been very active in the last several years, embarking on a 2½-year long tour from 2008 to 2010 and releasing three albums in the last four years of his life. These final albums make up a kind of trilogy in that they're similar in style and tone and each released two years apart, culminating with You Want it Darker.

Leonard Cohen - Image via billboard.com

The man who penned the famous line "There is a crack in everything—that's how the light gets in" (from "Anthem" on The Future), has, like many poets, indeed written numerous lyrics about darkness and light. Cohen once commented that he thought he'd finally realized the meaning of the word "enlightenment", concluding that maybe it just means to "lighten up". It's a subject that Cohen was well-equipped to comment on; he was born and raised as a practising Jew, studied Hinduism in India, invoked numerous Christian and other religious themes in his work, spent years meditating and studying Buddhism on a mountain monastery, and was ordained a Buddhist monk. Enlightenment is a subject he's literally meditated on a lot. Indeed, folkster/poet/songwriter Bob Dylan—the friend and contemporary of Cohen's who he's been perhaps most compared to—once commented that Leonard's songs were "like prayers". And here Cohen continues the examination of that theme in all its facets—light, dark, shadows, enlightenment, lightening up, and darkening down—immediately evident in the album's title and opening track of the same name, "You Want It Darker".

The song begins with Judaic chanting and a refrain of "Hineni hineni / I'm ready my Lord". "Hineni" is Hebrew for "Here I am", Abraham's answer to the summons of God to sacrifice his son Isaac. Among other things, it's a song about preparing for the end of religious devotion, and also, perhaps, preparing for the end of life. The chants and backing vocals are recordings of Gideon Zelermyer, the cantor at the Montreal synagogue which Cohen attended in his youth. So the song, and whole album, is at once spiritual and grand while also personal and intimate, and as such is a fitting final work for the master artist who paradoxically seemed to capture the ineffable through his words as the best writers do time and again.

With a haunting melody and pulsing beat, "You Want It Darker" emulates the sardonic tone so effectively evoked in Cohen classics "Everybody Knows" and "The Future". The first verse opens with: "If you are the dealer, I'm out of the game / If you are the healer, it means I'm broken and lame / If thine is the glory, then mine must be the shame / You want it darker / We kill the flame". The "you" that Cohen addresses here seems to be God itself, applying that old atheistic sentiment that a benevolent god surely can't exist given the immense suffering of so many in the world. But Cohen takes this idea and inverts it by way of a ironic sensibility, suggesting that perhaps God has been misinterpreted, and in fact wants "it darker". The lyrics "Magnified, sanctified, be thy holy name / Vilified, crucified, in the human frame" suggest though that God actually is a concept of higher truth that exists as a largely unattainable reality for our limited physical vessels—and furthermore, that God maybe actually depends on "darkness" in the physical realm in order to preserve "lightness" in some higher celestial plain.

It's a contradictory paradigm suggesting that positive and negative are inextricably linked concepts, and Cohen comments on this as an apparent attempt to make sense of the world's horrors. But he takes a satirical view of suffering, too, with the lyrics "I struggled with some demons / They were middle class and tame / I didn't know I had permission to murder and to maim". The mention of one's demons being "middle class and tame" suggests that our demons are perhaps often actually not as bad or as strong as we think, and there's the implication of not taking oneself too seriously. "There's a lullaby for suffering, and a paradox to blame," Cohen continues speak-singing in his trademark dry baritone voice, describing this complex reality of overwhelming contradiction. And so the song continually points to this idea that the darker things are in the terrestrial realm, the lighter they may be in another realm. While the lyrics superficially resound as dark and dismal, perhaps it's actually all about faith—in both a religious sense as faith in the existence of god, and also about faith as an ultimate belief that things will be okay despite evidence to support this. Or perhaps there's little difference between either of these interpretations of faith, anyway.

Leonard Cohen - Image via billboard.com

After introducing this thesis of facing demons in the darkness with "You Want It Darker", eight more majestic songs complete the album's nine. There's far less of the romantic loverman stuff that Cohen's famous for, and more of the poetic musings on mortality and God—fitting given he was an octogenarian while writing and recording the album. At his age, trying to maintain his sexyman role wouldn't work (although maybe a lot of his female fans would still go for it)—but with recent albums he's comfortably shifted instead into a gracious elder who's maintained quiet poignancy in his reminiscences on pain and loss—of faith, of love, of life—with greater focus on letting go. Death, rebirth, repentance, forgiveness all swirl throughout the album. Cohen's been given many titles, including "the high priest of pathos" and "godfather of gloom", having indeed battled the life-long affliction of depression. And this is evident in his work, eternally filled with expressions of longing and despair, tethering the ungraspable power of emotion in something that we can glimpse, even if only for a fleeting moment, through art.

The "you" who Cohen's narrator continues to address throughout the album ambiguously applies to a lover as much as to God. It seems he's addressing both; that there's no difference for love of God and love of another person, as the narrator analyzes the existence of each after the personal love has passed. The second track "Treaty" illustrates this with lyrics such as "I do not care who takes this bloody hill / I'm angry and I'm tired all the time / I wish there was a treaty / I wish there was a treaty / Between your love and mine". The melody is soft and piano-driven, contemplative and emotive—appropriate for a man of Cohen's age. And that melody returns as the album's last track in a near instrumental revisitation entitled "String Reprise/Treaty", which plays as a beautiful, stripped-down piece of classical music orchestration in which cello, viola, and violins sway together before Cohen's voice returns at the end to deliver a few lines concluding with "I wish there was a treaty between your love and mine."

The relationship between light and dark, and between physical love and spiritual love, is touched on time and again throughout the album, as in "On The Level" in which Cohen sings "When I turned my back on the devil, I turned my back on the angel too". Something profound is mixed in there, about facing demons as an unavoidable reality, which—when one can do it, really accept and face the darkness—results in ultimate sanctuary from pain, and a crumbling of such mortal human confines as good vs. bad, us vs. them, black-and-white ways of thinking.

Leonard Cohen - Image via hq.vevo.com

Another reigning theme is living with pain—emotional and/or physical, and the exploration of the cure to one's ailments as being, possibly, something spiritual, something lurking in the darkness that must be embraced—if not in this life then the next. This is exemplified by the lyrics of "Steer Your Way": "Steer your path through the pain / That is far more real than you / That smashed the cosmic model / That blinded every view / And please don't make me go there / Though there be a god or not / Year by year / Month by month / Day by day / Thought by thought".

"Steer Your Way" was published as a poem in The New Yorker before appearing as a song on the new album, indicative of Cohen's identity as perhaps a writer and poet foremost and a singer-songwriter second, since he had no formal music training. He's said that his songwriting was based on six chords he learned from a flamenco guitar-playing Spaniard Cohen met while in his twenties, who killed himself before their fourth lesson. And that six-chord progression, that guitar pattern, has been the basis of all his songs up to and including those on You Want it Darker. This is valuable to note for any up-and-coming artists; it's not necessarily the depth of musicianship, of technical skill or knowledge, that might contribute to a musician's success but rather, perhaps, the ways in which they can utilize the tools at their disposal to express their creative visions as clearly as possible. Indeed, Cohen's music has usually radiated a minimalist quality, the melodies more so complementing the lyrics than the other way around. He found an effective formula with it, making one really listen to what's being said. And it's okay if you don't catch every line because value comes by moments of emotional arousal through snippets of poetic imagery just as much as through careful analysis of each song as a whole. But despite Cohen's lack of technical musical depth, his songs are deep nonetheless, with recurring themes of suffering, sadness, grief, loss, compassion, yearning for meaning, and, most importantly, at the root of everything, love.

Part of what made Cohen successful as a ladies' man is that his romantic sentiments rarely came off as cheesy but rather as genuinely earnest expression and exploration of intimate relationships, anchored by a degree of modesty and self-effacement as evidenced with Cohen titles such as "Death of a Ladies' Man" (1977). There was often a measure of parody present; as much as he relished his regard as a ladies' man, he also made fun of it. Such humble self-degradations contributed to his allure as a man who acknowledged his status as being attractive to women while at the same time always striving to improve himself as a lover. He was honest about it, not showy or braggadocious, leaning towards expressing insecurity as a romantic partner more so than wallowing in romantic bliss. It's been said that he had an irresistible charm, with women no less with men.

In 1988's "Tower of Song" Leonard self-mockingly sings "I was born like this / I had no choice / I was born with the gift of a golden voice"—recognizing that his singing voice was never his appeal. While always registering a spoken word poetry/singsong kind of delivery more so than melodic singing, his voice grew considerably deeper in tone, more husky and breathy as he aged, to the point where he's basically speaking the lines rather than singing on his last few albums. But this speak-singing has continued to work, with Cohen's experience as a poet and writer placing him in a dimension where his voice and persona manifest as vehicles to deliver his words and music. As a poet, Cohen never stopped; he published over a dozen books of collected poems since his first in the 1950s to his last in 2012.

Leonard Cohen circa 2014 - Image via buffalo news.com

You Want it Darker is somewhat sparse, sonically, focusing less on percussion and more so on piano and strings-driven downtempo melodies, with frequent background female singers and occasional religious-inflected chanting. It's very, very slow. Cohen's music has generally been such, with the occasional more upbeat ditty, and here the slowness is effective as not only a reflection of Cohen's place in life as an aged, physically-ailed artist, but also as a collection of spellbinding, spiritual odes.

The softness in sound is complemented by dark reflections on god and mortality, with something that occasionally comes off as approaching nihilism; there's the thematic thread of questioning everything and rejecting meaning in both tangible and intangible universes. But maybe it's ultimately more so projecting a truly enlightened view, something reaching a higher plain of evolution and approaching the Buddhist concept of "nothingness"—a way to transcend physical form and achieve a state of consciousness as the spiritual beings who we really are. The Buddhist concept "Śūnyatā" has been translated into a number of related meanings, depending on doctrinal context; it can mean "emptiness", refer to the "not-self", to a meditative state, and to the experience of openness and understanding non-existence. So the metaphorical application of light and dark here, with a focus on the dark, is perhaps ultimately not as lonely and sad as it first registers, but rather the reflections of an elderly man striving for—and possibly actually having achieved—true peace by acknowledging and exploring the void, despite or maybe because of being in perpetual physical pain. So lyrics like those from "Leaving the Table" such as "I don't need a lover / So blow out the flame" at once resonate as melancholy ruminations of a solitary old man while also expressing surrender, freedom, and contentment through acknowledgment of this.

"It Seemed the Better Way" once again explores the theme of challenging/questioning truth and faith: "Seemed the better way / When first I heard him speak / Now it's much too late / To turn the other cheek / Sounded like the truth/ Seemed the better way / Sounded like the truth/ But it's not the truth today". It concludes with "I better hold my tongue / I better take my place / Lift this glass of blood / Try to say the grace". Sounds like the echoings of one who has lost belief in god, lost faith—or at least religious faith. But perhaps not spiritual faith. The difference between the two continues to bear extensive contemplation. And Cohen dives into that fully here, perhaps never so prominently and directly on one single album than ever before.

It all makes for a work that is a moving elegy, a fitting coda to the career of a legendary artist, as it further explores many themes that have been present in Leonard Cohen's work since the beginning. But it also has its own unique feel and sound, most similar to his previous two albums which also look at subjects of love, god, and death. "Traveling Light"—a brilliant double entendre title—is perhaps about death more than any other song on the album. It concludes with the lyrics "But if the road leads back to you / Must I forget the things I knew / When I was friends with one or two / Traveling light like we used to do / I'm traveling light".

• Nik Dobrinsky / Boy Drinks Ink

December 1st, 2016

Leonard Cohen - Image via thelehrhaus.com